They went hunting for fossil fuels. What they found could help save the world

When two scientists went looking for fossil fuels beneath the ground of northeastern France, they did not expect to discover something which could supercharge the effort to tackle the climate crisis.

Jacques Pironon and Phillipe De Donato, both directors of research at France’s National Centre of Scientific Research, were assessing the amount of methane in the subsoils of the Lorraine mining basin using a “world first” specialized probe, able to analyze gases dissolved in the water of rock formations deep underground.

A couple of hundred meters down, the probe found low concentrations of hydrogen. “This was not a real surprise for us,” Pironon told CNN; it’s common to find small amounts near the surface of a borehole. But as the probe went deeper, the concentration ticked up. At 1,100 meters down it was 14%, at 1,250 meters it was 20%.

This was surprising, Pironon said. It indicated the presence of a large reservoir of hydrogen beneath. They ran calculations and estimated the deposit could contain between 6 million and 250 million metric tons of hydrogen.

That could make it one of the largest deposits of “white hydrogen” ever discovered, Pironon said. The find has helped fuel an already feverish interest in the gas.

White hydrogen – also referred to as “natural,” “gold” or “geologic” hydrogen – is naturally produced or present in the Earth’s crust and has become something of a climate holy grail.

Hydrogen produces only water when burned, making it very attractive as a potential clean energy source for industries like aviation, shipping and steel-making that need so much energy it’s almost impossible to meet through renewables such as solar and wind.

But while hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, it generally exists combined with other molecules. Currently, commercial hydrogen is produced in an energy-intensive process almost entirely powered by fossil fuels.

A rainbow of colors is used as a shorthand for the different types of hydrogen. “Gray” is made from methane gas and “brown” from coal. “Blue” hydrogen is the same as gray, but the planet-heating pollution produced is captured before it goes into the atmosphere.

The most promising from a climate perspective is “green” hydrogen, made using renewable energy to split water. Yet production remains small scale and expensive.

That’s why interest in white hydrogen, a potentially abundant, untapped source of clean-burning energy, has ratcheted up over the last few years.

‘We haven’t been looking in the right places’

“If you had asked me four years ago what I thought about natural hydrogen, I would have told you ‘oh, it doesn’t exist,’” said Geoffrey Ellis, a geochemist with the US Geological Survey. “Hydrogen’s out there, we know it’s around,” he said, but scientists thought big accumulations weren’t possible.

Then he found out about Mali. Arguably, the catalyst for the current interest in white hydrogen can be traced to this West African country.

In 1987, in the village of Bourakébougou, a driller was left with burns after a water well unexpectedly exploded as he leaned over the edge of it while smoking a cigarette.

The well was swiftly plugged and abandoned until 2011, when it was unplugged by an oil and gas company and reportedly found to be producing a gas that was 98% hydrogen. The hydrogen was used to power the village, and more than a decade later, it is still producing.

When a study came out about the well in 2018, it caught the attention of the science community, including Ellis. His initial reaction was that there had to be something wrong with the research, “because we just know that this can’t happen.”

Then the pandemic hit and he had time on his hands to start digging. The more he read, the more he realized “we just haven’t been looking for it, we haven’t been looking in the right places.”

The recent discoveries are exciting for Ellis, who has been working as a petroleum geochemist since the 1980s. He witnessed the rapid growth of the shale gas industry in the US, which revolutionized the energy market. “Now,” he said, “here we are in what I think is probably a second revolution.”

White hydrogen is “very promising,” agreed Isabelle Moretti, a scientific researcher at the University of Pau et des Pays de l’Adour and the University of Sorbonne and a white hydrogen expert.

“Now the question is no longer about the resource… but where to find large economic reserves,” she told CNN.

A slew of startups

Dozens of processes generate white hydrogen but there is still some uncertainty about how large natural deposits form.

Geologists have tended to focus on “serpentinization,” where water reacts with iron-rich rocks to produce hydrogen, and “radiolysis,” a radiation-driven breakdown of water molecules.

White hydrogen deposits have been found throughout the world, including in the US, eastern Europe, Russia, Australia, Oman, as well as France and Mali.

Some have been discovered by accident, others by hunting for clues like features in the landscapes sometimes referred to as “fairy circles” – shallow, elliptical depressions that can leak hydrogen.

Ellis estimates globally there could be tens of billions of tons of white hydrogen. This would be vastly more than the 100 million tons a year of hydrogen that is currently produced and the 500 million tons predicted to be produced annually by 2050, he said.

“Most of this is almost certainly going to be in very small accumulations or very far offshore, or just too deep to actually be economic to produce,” he said. But if just 1% can be found and produced, it would provide 500 million tons of hydrogen for 200 years, he added.

It’s a tantalizing prospect for a slew of startups.

Australia-based Gold Hydrogen is currently drilling in the Yorke Peninsula in South Australia. It targeted that spot after scouring the state’s archives and discovering that back in the 1920s, a number of boreholes had been drilled there which had very high concentrations of hydrogen. The prospectors, only interested in fossil fuels, abandoned them.

“We’re very excited by what we’re seeing,” said managing director Neil McDonald. There is more testing and drilling to do but the company could get into early production possibly in late 2024, he told CNN.

Some startups are seeing eye-popping investments. Koloma, a Denver-based white hydrogen start-up, has secured $91 million from investors, including the Bill Gates-founded investment firm Breakthrough Energy Ventures – although the company remains tight-lipped about exactly where in the US it is drilling and when it is aiming for commercialization.

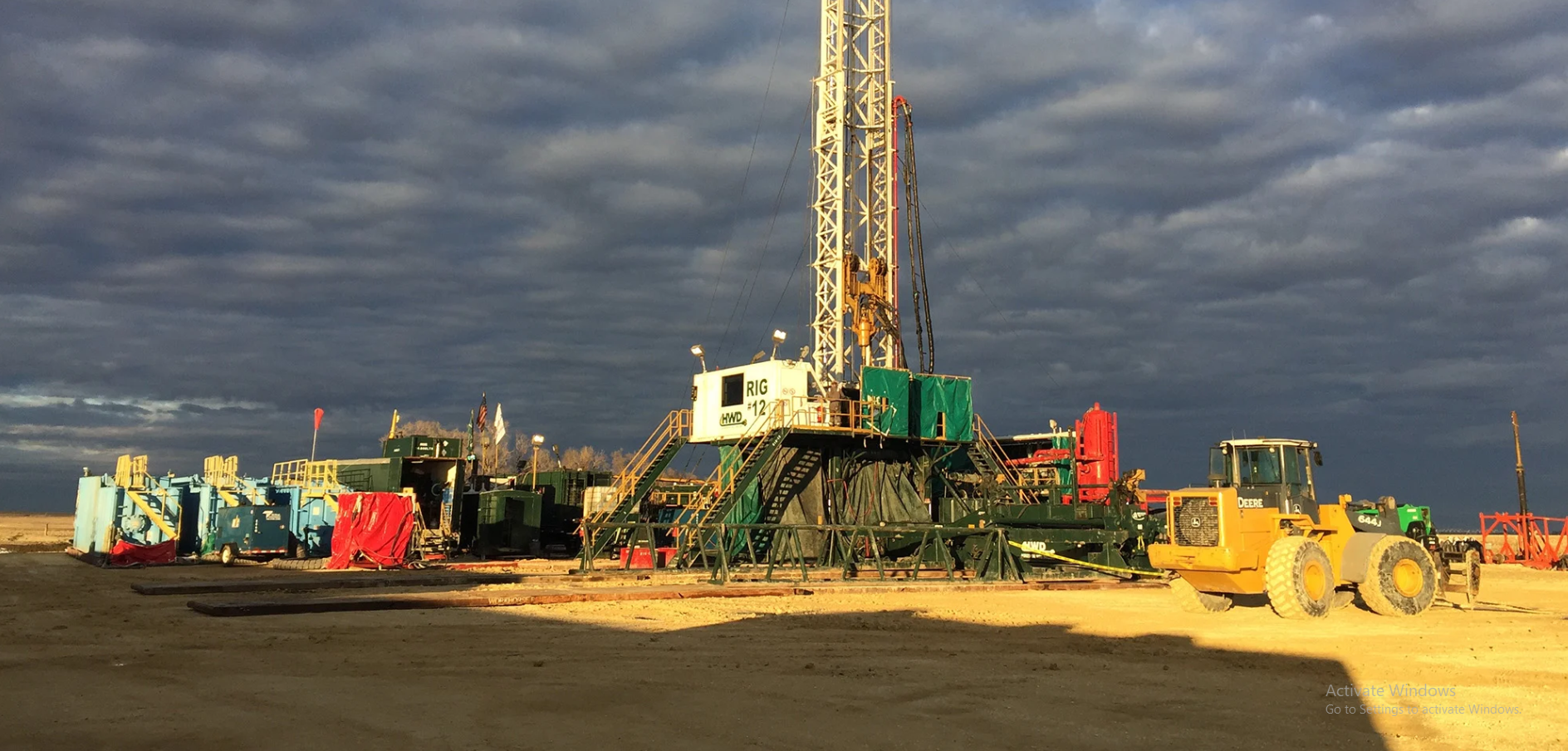

Another Denver-based company, Natural Hydrogen Energy, founded by geochemist Viacheslav Zgonnik, has completed an exploratory hydrogen borehole in Nebraska in 2019 and has plans for new wells. The world is “very close to the first commercial projects,” Zgonnik told CNN.

“Natural hydrogen is a solution which will allow us to get get to speed” on climate action, he said.

From hype to reality

The challenge for these businesses and for scientists will be translating hypothetical promise into a commercial reality.

“There could be a period of decades where there’s a lot of trial and error and false starts,” Ellis said. But speed is vital. “If it’s going to take us 200 years to develop the resource, that’s not really going to be of much use.”

But many of the startups are bullish. Some predict years, not decades, to commercialization. “We have all necessary technology we need, with some slight modifications,” Zgonnik said.

Challenges remain. In some countries, regulations are an obstacle. Costs also need to be worked out. According to calculations based on the Mali well, white hydrogen could cost around $1 a kilogram to produce – compared to around $6 a kilogram for green hydrogen. But white hydrogen could quickly become more expensive if large deposits require deeper drilling.

Back in the Lorraine basin, Pironon and De Donato’s next steps are to drill down to 3,000 meters to get a clearer idea of exactly how much white hydrogen there is.

There’s a long way to go, but it would be ironic if this region – once one of western Europe’s key coal producers – became an epicenter of a new white hydrogen industry.